- Home

- Helen Monks Takhar

Precious You

Precious You Read online

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are the products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events, locales, or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

Copyright © 2020 by Helen Monks Takhar

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Random House, an imprint and division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

Random House and the House colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Monks Takhar, Helen, author.

Title: Precious you: a novel / Helen Monks Takhar.

Description: First edition. | New York: Random House, [2020]

Identifiers: LCCN 2019032283 (print) | LCCN 2019032284 (ebook) | ISBN 9781984855961 (hardcover; acid-free paper) | ISBN 9781984855978 (ebook)

ISBN 9780593134542 (international edition)

Subjects: GSAFD: Suspense fiction.

Classification: LCC PR6113.O534 P74 2020 (print) | LCC PR6113.O534 (ebook) | DDC 823/.92—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019032283

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019032284

Ebook ISBN 9781984855978

randomhousebooks.com

Book design by Jen Valero, adapted for ebook

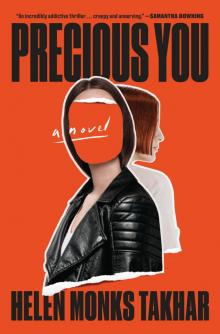

Cover design: Anna Kochman

Cover images: ta-nya/Getty Images (foreground woman); Matt and Tish/Stocksy United (background woman)

v5.4

ep

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Epigraph

Katherine

Chapter 1: Katherine

Lily

Chapter 2: Katherine

Lily

Chapter 3: Katherine

Lily

Chapter 4: Katherine

Lily

Chapter 5: Katherine

Chapter 6: Katherine

Lily

Chapter 7: Katherine

Chapter 8: Katherine

Lily

Chapter 9: Katherine

Lily

Chapter 10: Katherine

Chapter 11: Katherine

Lily

Chapter 12: Katherine

Chapter 13: Katherine

Lily

Chapter 14: Katherine

Lily

Chapter 15: Katherine

Chapter 16: Katherine

Chapter 17: Katherine

Lily

Chapter 18: Katherine

Chapter 19: Katherine

Lily

Chapter 20: Katherine

Lily

Chapter 21: Katherine

Chapter 22: Katherine

Chapter 23: Katherine

Chapter 24: Katherine

Lily

Author’s Note

Dedication

Acknowledgments

About the Author

SNOWFLAKE GENERATION

NOUN

informal, derogatory

The generation of people who became adults in the 2010s, viewed as being less resilient and more prone to taking offense than previous generations.

COLLINS ENGLISH DICTIONARY

Oh, little snowflakes, when did you all become grandmothers and society matrons, clutching your pearls in horror at someone who has an opinion about something, a way of expressing themselves that’s not the mirror image of yours, you sniveling little weak-ass narcissists?

BRET EASTON ELLIS

There is no one with a greater sense of entitlement than a millennial.

COMMENT UNDER DAILYMAIL.CO.UK ARTICLE, “MILLENNIAL FURIOUSLY RANTS ABOUT HOW MUCH EASIER LIFE WAS FOR HIS PARENTS”

A lot of offensive stuff is happening. Why should people not be offended? People are offended but they’re using that feeling of being offended to bring about change. Things are so dire sometimes that it’s necessary. If I want to carve out a safe space, why shouldn’t I?

LIV LITTLE, EDITOR, GAL-DEM.COM

I’ve lost you in the neon river of high-visibility vests and chrome helmets flying ahead of my car toward the junction. You lot all look the same. Is that what they think of us? I can hear Iain say. I fight my exhaustion, rub my gritty eyes, and try to find you again.

I slept in my car last night. I had that dream again, the one I told you about, the one I’ve had every night since I laid eyes on you. I’m back at my mother’s farm. A darkness soaks into my bones; a black sky marbled with thick red veins envelops me. Through the gloom, I see my top half is me today; a short swish of black hair, my strong arms shielded by a leather biker jacket. The bottom half is twelve-year-old me; my mother’s dirty cast-off jeans hanging off stringy legs. I’m starving. Barefoot, at first I’m treading on stubbled grass, but the terrain quickly changes; I’m stepping on burned pasture, like a thousand tiny razors under my bony feet. My blood begins to wet the parched scrub below. Suddenly, the ground begins to separate into hundreds of deep gullies. My instinct is to freeze, but I know I must go forward; ahead of me is the gate to the far paddock and I have to reach it to end this nightmare and stop my hunger. And I can’t see her, but I know my mother is watching. She thinks I’ll never make it. She thinks me too weak; she always tried to keep me so. She’s willing me to stop, but I keep pushing forward; despite the pain, despite the hungry chasms at my feet that want to swallow me, I force myself to place one foot in front of the other to reach the gate.

I woke up aching, bent double in the backseat of my Mini. My life has come to this because of you: an existence played out slumped in Costa armchairs and the car I can’t afford to insure anymore. This morning I’d decided to drive. I didn’t know where or why until I spotted you on your bike. Then, I knew exactly what I had to do.

I stop-start, tracking you through the clog of traffic edging toward De Beauvoir and into Shoreditch, then the City. At Liverpool Street you snake your way through stationary vehicles and out of my sight. Then, the jam begins to shift, allowing me to edge forward and mark you again, keeping just a few meters behind you as the traffic pushes down Gracechurch Street.

We’re nearly there.

Five cyclists have died on the junction ahead in the past year. Five young lives, just like yours, lost.

The car in front turns to give me free passage to the edge of the advanced stop line at the junction. I’ve got you in my sights. It’s as if the world has finally decided to take my side, but no sooner than I start to move forward, cyclists flood into the void ahead. I’m surrounded once more by glinting handlebars and fluorescent young bodies.

I’m stuck.

I search desperately for you up ahead, then in my rearview. But you’ve disappeared. You’re going to enjoy another day on this earth; another day in my job, going home to my flat, tucking yourself into the bed my partner and I chose together.

Then, there you are.

You’ve pulled up right next to my door, your eyes focused on the lights ahead. Your body, that close to me again, makes my blood rise. You’re inches from me. I could reach out, grab your arm, and beg you to tell me once and for all: Why? When I was ready to help you, why did you set out to snatch everything that was mine?

You start to

move away, squeezing through the other cyclists to the very front of the pack. You flash that smile of yours. Of course, they let you pass. That devastating smile.

That smile is like the warmest sun and the brightest light. That smile has undone my life.

Behind you, I move ahead too, breaching the cyclists’ zone and causing various slaps on my Mini’s roof and cries of What the fuck do you think you’re doing, you stupid cow? to erupt as I force them out of my path. You swivel around to see what’s causing the uproar, but quickly turn back toward the lights, knowing they’ll change any second. You don’t notice my car creeping up right behind you, and you don’t wait for the green light before deciding to strike out on your own; up off your seat, powerful calves bearing down onto the pedals as you begin your acceleration. But it’s time you were stopped from getting ahead of me.

Your back wheel fills my sight.

I wonder what your body will feel like under me, as your bones crunch and collapse. I can almost smell your blood, running hot in the final moments before it gushes from you, cooling as it flows out onto the tarmac to drip into the waiting drains and down to an impassive Thames.

Only when this happens can I really begin again.

The lights change to green. I slam my foot down hard on the accelerator.

SIX WEEKS EARLIER

I’ll never understand why they weren’t worried, those young things I saw every day at the bus stop, stretching free of their crammed houseshares and parental buy-to-lets in my neighborhood, at least a mile from the nearest place they would actively choose to live. Why didn’t they care we hadn’t seen a bus for twenty minutes? I made a mental note to ask Iain why no one under thirty seemed arsed about being late for work anymore, then texted my deputy, Asif. I was hoping he’d have words of reassurance, something I could use to soothe my latest work-related crisis. That Monday was the first day of a brave new world at the magazine I edited: new owners, a new publisher, a shot at a new start. I knew it was critical I made a good impression, but the world was already screwing this for me by making all the buses disappear.

I messaged Asif:

No bus. Confess late now or busk it?

And got back a not particularly helpful:

Nice weekend? New publisher already here. Not sure. Good luck. xxx

I can see myself that morning, gazing in the direction of my flat, the edges of its dried-out window boxes just visible from where I stood. I wore the oversized high-collared shirt I’d bought the day before, an ankle-length pencil skirt split to the thigh, and the black biker I always wore to work. I wanted to show up looking just-pressed, but edgy and not desperate to fit into the new corporate regime I was facing, even though, of course, I was.

Mondays were already hard for me, even before that day. It wasn’t just that after twenty years I seemed to be getting worse at my job, not better, nor that the youth, hope, and unbounded energy of my interns shoved the frustrated promise of my own formative years right back in my face with greater force every day. No, it was the awfulness, the horrifying dread, of the interns asking me, “What did you do this weekend?”

Compared to when I was at the height of my potential in my twenties, I felt invisible most of the time. But on Monday mornings I felt suddenly watched. I tried, as I so often did when I was surrounded by millennials, to minimize the damage to my pride. While they recounted their energetic tales of running around London, meeting other bright young things from north, south, east, and western corners, as I had once done, I sat tight. I had done next to nothing with no one but Iain, and this could be exposed at any second. I’d sometimes manage to arrange phone interviews for 9 A.M. on Mondays, so I could block out their weekend lives and avoid their social and creative endeavors showing up my dead existence. If anyone got to ask me The Monday Morning Question, I’d recently taken to out-and-out lying, telling the interns, “We caught up with some old friends.”

That Monday, my anxiety was soaring when I caught the glow of a taxi’s light far up the road. I watched it furtively at first, until I realized I was the only one inching toward the edge of the pavement to hail it. Of course, none of the bus stop lot had the money for a black cab. No money, but plenty of time. Their lives were rich with activities and all the time they had to do them: arts, crafts, queuing for artisan toast, curating photographic records of their fizzy lives on social media, and generally being creatively incontinent. I felt the hum of self-belief and productivity whenever I was around younger adults and it left me feeling singed.

I double-checked behind me for any would-be competitors for my cab. I saw you.

You were something quite different.

You had their air of creative confidence, the one I could only assume comes from parents who cheerlead your every trifling achievement, but you seemed to carry a hunger about you too; some neediness in your eyes. Out of nowhere, I got the sense you were a young person with whom I might possibly have some common ground.

Because unlike the others, you seemed like you were bothered by being late for work. Less like them, more like me. Such an odd sense of time and age I felt you emit: undeniably as young as them, but somehow seeming older and more desperate, like me, all at once. And do you remember, you wore that tiny leather skirt? I have one just like it and I used to wear it to work too. Your skin was as pale as mine, but fully taut and shimmering, except for a dirty stripe of oil on the right side of your forehead. I couldn’t take my eyes off you. You were like looking into a mirror, or more like a window into a different time in my life, not long past, but just out of reach. I wanted to know more about you, to see if you really could be anything like me. When the taxi began to pull over, I began to wonder if I should invite you to share it.

I glanced back at you again. A finger on your left hand fiddled with the string tag on the yellow laptop case you held against the front of your thighs. You switched your weight from hip to hip and occasionally flicked the nails of your right thumb and index finger under your chin. I took the door handle and turned around to take you in one last time, before the ebb and flow of a London day separated our paths. A thought needled its way to the front of my mind: your face would return to me throughout the day and I’d have to exorcize you by telling Iain over dinner about The Girl I Saw at the Bus Stop Who Reminded Me of the Old Me.

But you were watching me.

As you looked over, you bit your bottom lip, painted hot orange like the sunrise in summertime, and flicked your nails against your skin again before moving your black eyes off me to the nonexistent bus on the horizon.

I could let you into my cab, but I wondered what we would possibly talk about. Or maybe you’d just sink into your phone, like people your age do, and I wouldn’t get to talk to you at all. And how would you pay your way? People like you never have cash on them, so would I give you my bank details so you could transfer your share of the fare? Was that wise? Was that cool? Wasn’t there an app for that, one I’d be embarrassed to say I haven’t downloaded or even heard of yet? Or would you ask to meet me somewhere at lunchtime to give me my twenty quid? Would we then end up having a burger? Find ourselves talking for ages?

Go on, girl, you show ’em what us old ravers are made of, I could hear Iain say.

No.

No, I should leave it.

I didn’t need to overcomplicate what was already shaping up to be another day I’d want to forget. I opened the taxi door and readied myself to leave you on the pavement, but suddenly you were there, right behind me.

You made me jump.

“Hi there, you must be heading south? Mind if I get in?” When you spoke to me, your mouth split to reveal the most fantastic teeth.

“Yes. I mean, I’m heading to Borough, but—”

“Perfect. Me too. Wait a sec, sorry, I’ve just realized, I literally don’t have any cash.”

Behind you I saw that the bearded and big-ha

ired gaggle were agog that you’d thought of hitching a ride and they hadn’t. If I refused you, I feared a group of them would initiate some kind of collective action, gathering their grubby coins together in a bid to get in.

“It’s fine, just get in.” One of you had to be better than three or four.

“Is that all right? You’re absolutely sure?”

You gained and double-checked my consent. It was a technique you would use again and again on me when I didn’t understand what I was agreeing to. One of your many gifts.

“Sure.”

I obediently slid over to the far seat to make room for you. You bent low to get in, your head suddenly so close to mine I could smell you’d just washed your hair. It was still wet at the roots, cooling the blood in your scalp. I was about to tell the cabbie where to go, but your youthful scent made me falter.

“Borough, please. I’d avoid Old Street if I were you. Dalston, then Gracechurch?” you said. Smiling, you waved your phone in my direction. “Good for you? I’ve just seen there’s a burst water main near City Road. I mean, if you’d rather go your way?”

I saw your screen was blank.

I looked to the driver for some response, but was distracted by the faint reflection on the glass screen in front of me: a decidedly middle-aged woman, short ink-black hair framing a smudgy face. I was struggling to recognize myself again. I hadn’t admitted to Iain yet, but in the buildup to that day, I could feel my illness creeping back with its full force, exactly how it had when the last crash happened fifteen months ago.

Precious You

Precious You